For many reasons 2020 will loom large in future textbooks on financial history.

This year saw the biggest drop-off in economic output since the Great Depression, the biggest spate of money printing in the Federal Reserve’s 107-year history spurred by a coronavirus pandemic, an epochal shift toward remote working and negative prices for crude oil futures.

Perhaps as important in the pantheon of monetary milestones, 2020 saw the first real signs banks, money managers, insurance firms and companies started to embrace fast-growing markets for cryptocurrencies and digital assets.

An open-source software programmer going by the name Satoshi Nakamoto designed bitcoin (BTC, -0.57%) 11 years ago, the first cryptocurrency. It was built atop a cryptography-based “blockchain” network that could support a peer-to-peer electronic payments system, one that wouldn’t be under the control of any single person, company or government.

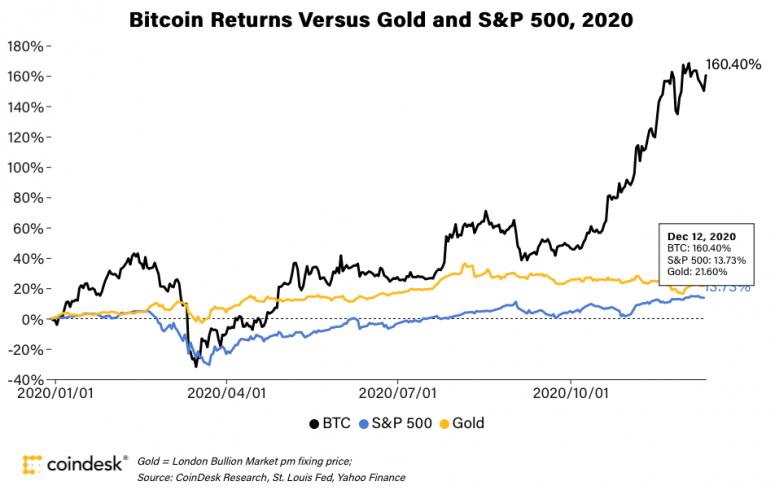

At the start of the year, bitcoin was still considered a fringe investment, disparaged by the likes of the billionaire investor Warren Buffett as having “no value.” By the end of the year, however, bitcoin has nearly quadrupled in value, reaching an all-time high above $28,000 and thrusting itself into the center of conversations among big investors and Wall Street firms.

Some bitcoin proponents saw the success of the cryptocurrency and its underlying blockchain network as validation of a landmark technology that might forever change finance.

But what changed bitcoin’s price trajectory in 2020 was its growing adoption as a hedge against the potential currency debasement that might come from trillions of dollars of coronavirus-related stimulus payments from central banks and governments around the world.

The thesis derives from the hard-coded limits on bitcoin’s supply, which are programmed into the underlying blockchain network. Unlike government currencies that can be issued subjectively and at will by central bankers, only 21 million bitcoins can ever be created.

And bitcoin’s growing adoption as an asset that trades based on macroeconomic trends meant it provided investors and analysts with as good a prism as any through which to view the year’s monumental economic developments and rapidly shifting financial landscape.

In the years before COVID-19 hit, low interest rates and the U.S. dollar’s reign as the global reserve currency allowed the U.S. government and its corporations to amass a heavy debt load that many observers warned was unsustainable. Once the pandemic hit, authorities’ response was to invoke what one leading economist described as the “war machine”: a Federal Reserve willing to finance U.S. government emergency-relief packages – and budget deficits – in the trillions of dollars.

Eventually, markets from stocks to bonds became hooked on the expectation that stimulus would be provided in amounts needed to keep investors from suffering losses deep enough to impair confidence and derail the economic recovery. As national authorities and monetary policymakers kept promising more and more stimulus, bitcoin’s price went up.

The cryptocurrency’s outperformance through it all eventually attracted the notice of big traditional finance players including JPMorgan Chase, BlackRock, AllianceBernstein, Morgan Stanley and Tudor Investment, which responded by buying billions of dollars of the previously scorned asset and flattering it with bullish research reports.

Whether due to causation or correlation or merely wishful thinking, the bitcoin market, long viewed as a hotbed of volatility and unfettered speculation, seemed to rise in 2020 with nearly every new headline.

The story of bitcoin in 2020 might be a classic tale of how a new technology emerges at the fringe, gradually wins the attention of a few well-heeled and respected money managers, then suddenly gets swept up by the rest of Wall Street, heralded as the next frontier for savvy investing and fast profits.

Trillions of dollars of money printing this year by the Federal Reserve and other central banks have galvanized bitcoin’s use as a hedge against currency debasement by investors from both cryptocurrency markets and traditional finance.

But even before the pandemic-related economic stimulus hit global markets, economists were already openly speculating whether the U.S. dollar could survive another decade as the world’s dominant currency for international payments and foreign reserves.

Historically, major world events and shifts in the geopolitical balance of power had always led to one currency supplanting another as the world’s most important medium of transaction, unit of accounting and store of value. The U.S. dollar had emerged as the world’s leading currency during the early 20th century when it took over from debt-strapped Britain’s pound sterling. A century before that, Holland’s guilder was undone by the French Emperor Napoleon’s invasion.

In early 2020, China’s proposed digital currency was seen as a potential threat to the greenback, and former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney went so far as to propose a “synthetic hegemonic currency,” potentially provided “through a network of central bank digital currencies.”

“There’s a lot of discussion of substitutes for the dollar as the global reserve currency,” Bill Adams, senior international economist for the U.S. bank PNC, told CoinDesk around the start of the year.

But based on officials tallies of the dollar’s share of global foreign reserves, the U.S. currency looked as strong as ever.

It didn’t take long in 2020 for the bitcoin market to get a jolt – after a U.S. drone strike killed a top Iranian commander during the first week of January, fueling speculation that heightened geopolitical turmoil might spur demand for the cryptocurrency. Bitcoin jumped to $7,300 as analysts said it might serve as a safe-haven asset similar to gold, whose value is expected to hold in times of geopolitical or economic instability.

Though the price gains held, the flap soon faded from the news and crypto traders turned to what they thought would be the bitcoin market’s marquée event of the year – the once-every-four-years “halving,” where the pace of new supply of cryptocurrency issued from the Bitcoin network would get cut by 50%. The process, hard-coded into the blockchain’s underlying programming, was expected to occur in May.

In the month leading up through February, Google searches on the term “bitcoin halving” had doubled to their highest levels since 2016, and some enthusiasts even created a dedicated website, bitcoinblockhalf.com, to count down the remaining days, hours, minutes and seconds until it happened.

Cryptocurrency lenders reported a quickening pace of customer activity, in some cases more than 10 times the loan growth reported by big banks like JPMorgan Chase. The flip side was Wall Street firms and banks were stuck with the traditional economy, where U.S. growth had slowed to 2.3% in 2019 from a 2.9% clip in 2018. (Although the economy was decelerating, a newly launched futures contract focused on the U.S. presidential election, launched by the cryptocurrency exchange FTX in early February, suggested Donald Trump had a 62% chance of winning.)

Bitcoin traders, many of whom had long since written off the stock market, bandied about analyst predictions that the halving could send prices skyrocketing to $90,000 or higher.

They had no idea, of course, how dramatically the events of the ensuing months would reshape the global economic outlook. By late February, traders saw clearly just how far bitcoin was from being a safe haven: Prices suddenly tumbled alongside U.S. stocks as authorities globally struggled to stem the spread of the coronavirus beyond China. U.S. Treasury bonds, seen as a traditional safe-haven asset, rallied. So did gold.

Bitcoin is “not the same as owning Treasury, and not the same as owning gold,” the cryptocurrency analyst Greg Cipolaro told CoinDesk on Feb. 24.

Jeff Dorman, chief investment officer of the crypto-focused firm Arca Funds in Los Angeles, raised the prospect of a separate potential catalyst for higher bitcoin prices: Monetary-policy easing by the Federal Reserve to stimulate coronavirus-infected markets. Since the cryptocurrency’s ultimate supply was controlled by the blockchain’s underlying programming, it couldn’t be inflated away by central bankers or any other humans, the reasoning went.

“I don’t expect bitcoin to trade as risk-on or risk-off asset,” he said. “But over a longer period of time, anything that’s inflationary, or, said another way, devalues other currencies, strengthens the purchasing power of bitcoin.”

Cipolaro, the analyst, who now works for the cryptocurrency-focused fund NYDIG, says he realized at some point in early March just how devastating the coronavirus might be to the global economy – and started mapping out what the might mean for the bitcoin market. Global authorities were struggling to contain the unusually contagious and deadly virus outbreak. Cipolaro even built his own spreadsheet to keep track of the rising case count.

Bitcoin, whose prices had hit a five-month high around $10,500 in February, slipped below $8,000. Initially, the decline seemed like no big deal in notoriously volatile digital-asset markets, especially since global stock markets were getting hit, too.

“There’s certainly a bit of fear in the bitcoin market, but it’s not anything close to the panic we’re seeing on Wall Street today,” Mati Greenspan, founder of the analysis firm Quantum Economics, which specializes in cryptocurrencies and foreign exchange, said at the time.

What happened next was one of the swiftest and deepest sell-offs in the history of global markets. On March 12, bitcoin prices plunged 39% in a single day, eventually hitting a low of $3,850.

With stocks and bonds also in upheaval, global authorities swung into action – determined to keep the financial system from freezing up, since such a calamity might deepen the economic damage or further impair confidence among investors, business executives and households. Primarily, the response came in the form of trillions of dollars of stimulus pumped into markets by the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan and authorities around the world.

As intended, asset prices came roaring back. And so did bitcoin. By the end of April, the cryptocurrency had more than doubled to about $8,600.

That’s when the cryptocurrency startups started getting phone calls from Wall Street. Bitcoin, whose ultimate supply is capped at 21 million under the underlying blockchain network’s programming, was getting a fresh look from big investors as a potential hedge against central-bank money-printing and currency debasement. The idea was it could serve as a modern and theoretically more portable version of gold.

“I’m getting calls from real big investors we’ve never seen before, saying, ‘Tell me about this bitcoin,’” Michael Novogratz, CEO of the cryptocurrency firm Galaxy Digital, told CNBC on April 2.

Economists wrestled with the question of whether deflationary forces might overwhelm any inflationary impulse because the coronavirus-related lockdowns might decimate consumer and business demand – a dynamic that often puts downward pressure on prices. At an even broader level, financial historians rekindled discussions over whether the new crisis might precipitate a change in the dollar-dominated global monetary order, similar to the Bretton Woods agreement toward the end of World War II.

“I wouldn’t rule out anything at this point,” Markus Brunnermeier, a Princeton University economics professor who has advised the International Monetary Fund, Federal Reserve Bank of New York and European Systemic Risk Board, told CoinDesk in late March.

Stephen Cecchetti, who headed the monetary and economic department at the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland in the early 2010s, articulated a key concept that has lurked in the bitcoin market commentary ever since: In times of deep turmoil, the presumption of central bank independence is largely ignored, allowing money printing to finance government budget deficits racked up due to emergency relief spending.

“The central bank has to be a part of the war machine,” Cecchetti, now a professor of international economics at Brandeis University, told CoinDesk.

The dynamic helps explain why bitcoin often swung this year alongside traditional markets depending on the on-again, off-again talks in Washington over new government-funded stimulus packages.

Some 10 months after the coronavirus pandemic hit global markets and the economy, the Federal Reserve is still using freshly printed (electronic) money to buy U.S. Treasurys and government-backed mortgage bonds, currently at a rate of $120 billion a month.

In doing so, the central bank is indirectly financing the U.S. government’s budget deficit, which surged to a record $3.1 trillion in the fiscal year ended Sept. 30, more than twice the prior record of $1.4 trillion set in 2009. The Congressional Budget Office has forecast a deficit of $1.8 trillion for the current fiscal year, remaining above $1 trillion every year through 2030. U.S. government debt held by the public, which started 2020 at an already-lofty $23 trillion, has now surged to about $27 trillion, and some bond-market analysts predict the Federal Reserve might need to keep monetary policy unusually loose for years to come – just so the Treasury Department can afford its interest payments.

The dynamic, set in motion in March and April, continues to prompt more of those phone calls to crypto startups from Wall Street. Earlier this month, Bank of America published a survey of fund managers showing that “long bitcoin” was one of the most “crowded trades” in global markets, along with “long tech” and “short dollar.”

“Over the course of 2020, many institutions have started to endorse bitcoin,” the cryptocurrency analytics firm Coin Metrics said in a report. “One of the most commonly cited reasons for this change of tune is the growing narrative that bitcoin could serve as a good hedge against inflation.”

As May arrived, the Bitcoin network’s upcoming “halving” seemed like an afterthought compared with the steep economic toll of the coronavirus.

It was all very technical, but the process would go something like this: When the blockchain ticked off its 630,000th data block, the pace of new issuance of bitcoin awarded to network supporters – known as “miners” – would get cut in half. Specifically, the issuance would fall to about 6.25 bitcoins every 10 minutes or so from the 12.5-bitcoin average clip that had prevailed over the recent four-year period.

Generally speaking, few surprises were expected, since all the details had been stipulated at the network’s outset. But that was the point: Under the cryptocurrency’s design, things were supposed to run like clockwork, giving humans little leeway to intervene based on subjectivity or politics.

Cryptocurrency market analysts talked up the halving as a potential catalyst for a price rally; one German bank had gone so far as to predict that bitcoin prices could shoot to $90,000 or higher.

“Look for prices to attempt the $10,000 level on speculative buzz leading into the halving,” Jehan Chu, co-founder and managing partner at Hong Kong-based blockchain investment and trading firm Kenetic Capital, told CoinDesk in late April.

CoinDesk even built its own “Bitcoin Block Reward Halving Countdown” to mark the estimated time and date of the big event. With everything going on in the world, the halving took on the feel of a geek-fest for crypto insiders. The suspense came mainly from watching the price charts: Would the halving drive bitcoin prices to the moon?

As it turned out, the halving came on May 11 and proved anticlimactic by pretty much all accounts. Industry executives on a CoinDesk halving-countdown talk show, held via Zoom, had to pass the time with technical discussions of the future potential of bitcoin mining computers and how much the network’s speed might accelerate over the next four years.

When the blockchain network finally reached block number 630,000, the moment everyone was waiting for, someone posted a snippet of code on Twitter showing the halving had indeed happened. There were some huzzahs all around, and everyone dropped out of the Zoom room.

“This is more of a holiday for the crypto community than anything else,” said Greenspan of Quantum Economics, in a note to clients.

Over the course of the month, prices never climbed much above $9,000.

“We are seeing buy-the-rumor, sell-the-fact at work,” Russell Shor, a senior market specialist at the foreign-exchange and cryptocurrency-trading firm FXCM, said in emailed comments.

Underneath the deflating buzz, though, was an epiphany: The blockchain network was working exactly as designed, and not even the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression had thrown it off course.

What’s more, the reduction in the pace of bitcoin issuance provided a sharp contrast with the monetary policies pursued by the Federal Reserve and other major central banks.

The human central bankers, to their credit, were doing all they could to keep the world’s financial system from collapsing. But the dynamic meant that bitcoin, with its hard-coded and ever-diminishing supply curve, might serve investors as a bulwark against debasement of the U.S. dollar and other currencies.

To underscore the point, the Chinese bitcoin-mining pool f2pool embedded a message into the blockchain record for data block No. 629,999: “NYTimes 09/Apr/2020 With $2.3T Injection, Fed’s Plan Far Exceeds 2008 Rescue.” It was a headline for a news article from the prior month, detailing a massive money-printing episode by the U.S. central bank.

Coin Metrics, a cryptocurrency analysis firm, revisited the theme in its report this month, noting how the blockchain’s quadrennial halvings might provide confidence to investors looking for an asset that isn’t subject to human discretion and qualitative judgments.

“Halvings will keep occurring every four years until the supply cap of 21 million bitcoin has been reached,” the analysts wrote. “This means we can project well into the future, and have clarity about what Bitcoin’s inflation rate will look like one, five or 10 years from now.”

By the end of May, bitcoin prices were sitting on a 35% year-to-date gain, following a series of wild market gyrations during an undeniably tumultuous and horrific year. With the coronavirus-racked U.S. economy suffering its worst contraction since the Great Depression, not even the bulls were in a mind to complain; the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index of U.S. stocks was down more than 6%.

Then, suddenly, the bitcoin market went cold. And that’s when the summer of DeFi began.

Decentralized finance is a subsector of the digital-asset industry where entrepreneurs are building semi-autonomous lending and trading systems atop decentralized networks, primarily the Ethereum blockchain. The whole ecosystem is built around digital tokens that can usually be passed around anyone with an Internet account.

Blockchain networks use distributed ledger technology, which are really just shared databases stored on multiple computers or “nodes,” in contrast with the central computers maintained by banks to hold account information. If the shared database shows a token belongs to me, and I sell it to you, and the database is updated to reflect the fact that you now own it, then I have effectively just sent it to you; as long as the database is secure, the transaction is complete, and now you can send it to someone else. It really is that simple.

The goal is to create alternatives to the big banks and trading firms that are centrally managed by human executives and boards of directors in places like New York, London and Tokyo. The idea is that the distributed, computer-based versions of crucial financial-system infrastructure should be fairer and more efficient to use than their old-world Wall Street counterparts, famously rife with excessive risk-taking as well as market manipulation of even giant, mature markets like foreign exchange and government bonds.

In the U.S. and elsewhere, venture capitalists have poured billions of dollars into the newfangled DeFi systems, convinced that the fast-paced growth of digital-asset markets might represent a haven of innovation and competition in an otherwise stagnant and clubby global banking system.

The first sign of the DeFi frenzy arrived in mid-June, when the autonomous lending platform Compound, started in 2017, released its proprietary COMP tokens for public trading in digital-asset markets. At the time, users had socked some $163 million of collateral into the project in exchange for loans. But what got everyone’s attention was a flurry of trading in the tokens that suddenly gave Compound a market capitalization of nearly $785 million.

Compound’s outsized market cap, relative to the total value locked in the protocol, “may signal the rally went too far,” The Defiant, a newsletter tracking the DeFi sector, wrote on June 16.

Even Compound’s 35-year-old founder, Robert Leshner, acknowledged the hysteria: “Because the asset was so new, there was a bit of a speculative fervor,” Leshner told CoinDesk in an interview.

It was just the beginning. Two days later, according to the website DeFi Market Cap, the project’s value had reached $2 billion, twice the amount that traditional investors in stock-oriented markets consider the threshold for a “unicorn,” a privately held startup with a valuation of at least $1 billion.

“DeFi is hitting its stride and the space will continue to accelerate,” the research firm Delphi Digital wrote in a report.

And bitcoin? Suddenly an afterthought.

“It’s surprising to see bitcoin be so boring given everything happening both within and outside the crypto industry,” the digital-asset analysis firm Messari wrote in its daily email to subscribers.

In mid-July Messari published a chart showing the Ethereum blockchain’s daily settlement value surging to about $2.5 billion, surpassing Bitcoin’s.

Prices began to soar not just for ether (ETH, +19.3%), the Ethereum blockchain’s native cryptocurrency, but for a veritable parade of tokens associated with hitherto little-known DeFi projects Aave, Chainlink, Curve and good-luck-explaining-this-to-your-friends outliers like Yam and Spaghetti.

Traditional investment analysts and Wall Street Journal columnists were now asserting matter of factly that U.S. stocks were merely being propped up by the Federal Reserve’s $3 trillion of money printing. So the DeFi explosion raised the question of whether the anything-goes digital-asset markets had become the new home of capitalism.

“Every derivatives trader that was looking for incremental yield and levered returns has been besotted by the magnitude of moves in DeFi,” Vishal Shah, founder of derivatives exchange Alpha5, told CoinDesk at the time. “So, naturally, cost of capital dictates at least some attention that way.”

Big cryptocurrency exchanges such as Binance started rolling out DeFi-related offerings to supplement their bitcoin-denominated trading operations. Yearn.finance, a just-invented protocol designed to steer users toward the highest-yielding DeFi projects, saw prices for its YFI token jump eightfold in August alone.

The headlines just kept getting zanier and more incomprehensible; even old crypto pros could barely keep up. A decentralized project called SushiSwap mounted what was described as a “vampire mining attack” to suck some $800 million of liquidity from another decentralized trading protocol called Uniswap.

Weeks later, Uniswap made a surprise delivery of its UNI tokens to anyone who had ever used the platform, worth at least $1,200 in market value – prompting some witty commentators to call it “stimulus for Ethereum users,” since it was the same amount as the coronavirus aid checks mailed out earlier in the year by the U.S. Treasury Department. Seemingly out of nowhere, and without the usual fanfare and Wall Street underwriting fees that typically accompany a big initial public stock offering, Uniswap had a $5 billion valuation.

Among digital-asset traders, bitcoin looked to be on the defensive, described as a “pet rock” because so little of the fast-paced DeFi development was taking place on its blockchain. Some bitcoin traders started converting their holdings into freshly minted digital tokens so that their “tokenized” versions of the cryptocurrency could be deposited on DeFi systems in exchange for juicy interest rates.

In hindsight, the summer of DeFi galvanized bitcoin’s appeal on a variety of fronts.

For one, it reinforced the reality that while bitcoin was the oldest and biggest cryptocurrency, it was hardly the most interesting. The digital asset industry and market infrastructure had matured to the point that the competition looked genuine; rival projects were proving capable of fast-paced innovation, disruption and growth.

“In 2020, DeFi put in place the building blocks for an entirely new financial system: payments, lending, asset issuance and exchange,” Messari’s Ryan Selkis wrote on Dec. 15.

The bullish twist was that bitcoin, as the first purchase for many cryptocurrency buyers, might be the gateway to a far-more lucrative industry than previously imagined.

The DeFi frenzy also sharpened many investors’ focus on what might be bitcoin’s most-compelling use case – as a tool for hedging against central bank money printing.

As the rest of the year would demonstrate, that “digital gold” narrative would prove enticing enough to big Wall Street firms and money managers to send bitcoin prices to a new all-time high. It might be a pet rock, but apparently a cute one that a lot of people wanted to hold.

As of early October, bitcoin prices were trading around $10,800, up 50% on the year. It was already an impressive gain, especially during a year when the global economy had suffered its worst contraction since the Great Depression nearly a century early. U.S. stocks were up 4%.

Despite the outperformance, bitcoin analysts were still bullish. The blockchain network was growing, brokers cited continuing interest from buyers, positive-looking patterns were forming in price charts, options markets were hinting at further gains, the dollar was weakening in foreign-exchange markets, and there were few signs that governments and central banks would curtail the seemingly endless flow of stimulus money anytime soon.

Yet, as of early October, few traders were betting that prices would more than double over the next three months, blowing past $20,000 to a new all-time high.

And then, something changed: big corporations and money managers started to pile into bitcoin, accompanied by a flurry of recommendations from once-skeptical Wall Street analysts.

Michael Saylor, CEO of a hitherto little-discussed outfit called MicroStrategy, shifted at least $425 million of his company’s corporate treasury into bitcoin. Square, the payments company, said it would put some $50 million, or 1% of its assets, into the cryptocurrency. PayPal, another payments company, announced it would allow 346 million customers to hold bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, and to use the digital assets to shop at the 26 million merchants on its network.

“It’s the sheer scale of PayPal’s reach that is attracting the headlines,” Jason Deane, an analyst for the foreign-exchange and cryptocurrency analysis firm Quantum Economics, wrote in a report in late October. “This could well go down in history as a watershed moment, the point at which bitcoin goes properly mainstream.”

Analysts with JPMorgan, whose CEO Jamie Dimon had famously called bitcoin a “fraud” in 2017, wrote that the cryptocurrency had “considerable” price upside. “Even a modest crowding out of gold as an alternative currency over the longer term would imply doubling or tripling of the bitcoin price from here,” they wrote.

Additional endorsements would flow over the coming months from the hedge-fund legend Stanley Druckenmiller, money managers SkyBridge Capital and AllianceBernstein, brokerage firm BTIG and life-insurance company MassMutual. Wells Fargo, the big U.S. bank, published a 2021 investment outlook with a full page discussing bitcoin’s big gains, even though executives said customers weren’t allowed to buy it in their accounts due to regulatory uncertainty.

“I think cryptocurrency’s here to stay,” Rick Rieder, chief investment officer for the big mutual-fund company BlackRock, told CNBC on Nov. 20.

Joe Biden’s victory in the U.S. presidential election reinforced investors’ belief that government stimulus money would continue for the foreseeable future, since the candidate had pledged to push for at least $5 trillion of new spending initiatives from education to housing, health care and infrastructure.

In December, the Federal Reserve adopted “qualitative” guidance for its $120-billion-a-month of asset purchases – a form of monetary stimulus that relies on money printing. The new guidance gave policy makers additional flexibility to continue the program as long as they deemed fit.

Prices for bitcoin shot past $20,000 on Dec. 16, setting a new price record, and within days had surpassed $23,000. As of Wednesday, the cryptocurrency was changing hands at $28,085.

“Bitcoin has graduated from ‘digital assets playground’ to ‘mainstream global investment,’” Dorman, the Arca chief investment officer, wrote this month in an op-ed. “Investors now have the knowledge and means to buy bitcoin themselves, and we are seeing it in real-time, which happened quicker than we anticipated.”

What comes next? Analysts are still bullish.

Dan Morehead, CEO for the cryptocurrency-focused money manager Pantera, recently cited a formula that projects a price of $115,000 by next August. Scott Minerd, chief investment officer for the Wall Street firm Guggenheim, predicted bitcoin could go to $400,000.

The cryptocurrency investment firm NYDIG published an analysis arguing that the Bitcoin network’s growth could justify prices in the range of $51,611 to $118,544 in five years. Kraken Intelligence, a research unit of the digital-asset exchange Kraken, published results of a survey noting that clients expect an average bitcoin price of $36,602 in 2021.

Even the Kraken customers’ comparatively modest prediction would represent a 30% gain from current price levels. That might mean bitcoin outperforms again in 2021, with Wall Street analysts on average predicting a 9% return for U.S. stocks next year.

A once-in-a-generation calamity like the coronavirus was bound to create extreme gyrations in global markets, with some assets proving big winners and some losing big. (Remember the mortgage market in 2008, and “The Big Short“?)

In hindsight, bitcoin was the biggest winner from the coronavirus crisis of 2020, especially with few analysts projecting that the economy will return to its former strength anytime soon. If that’s the case, it’s possible that trillions of dollars of stimulus from governments and central banks around the world might be needed on an ongoing basis to nurse any recovery.

“The current macroeconomic environment is set up perfectly for an asset that blends the benefits of technology and gold,” the U.K. money manager Ruffer Investment said in a recent portfolio update, after confirming a bitcoin purchase worth more than $745 million. “Negative interest rates, extreme monetary policy, ballooning public debt, dissatisfaction with governments – all provide powerful tailwinds.”

Bitcoin marketeers couldn’t ask for a more compelling selling point. As if this year’s quadrupling in price isn’t compelling enough.